The great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges believed Buenos Aires to be “as eternal as water and air.” This detachment from time can be found in traditions and arts that seem to have been here as long as the city itself, and which continue to thrive. Traditions such as the fileteado.

The resurgence of tradition

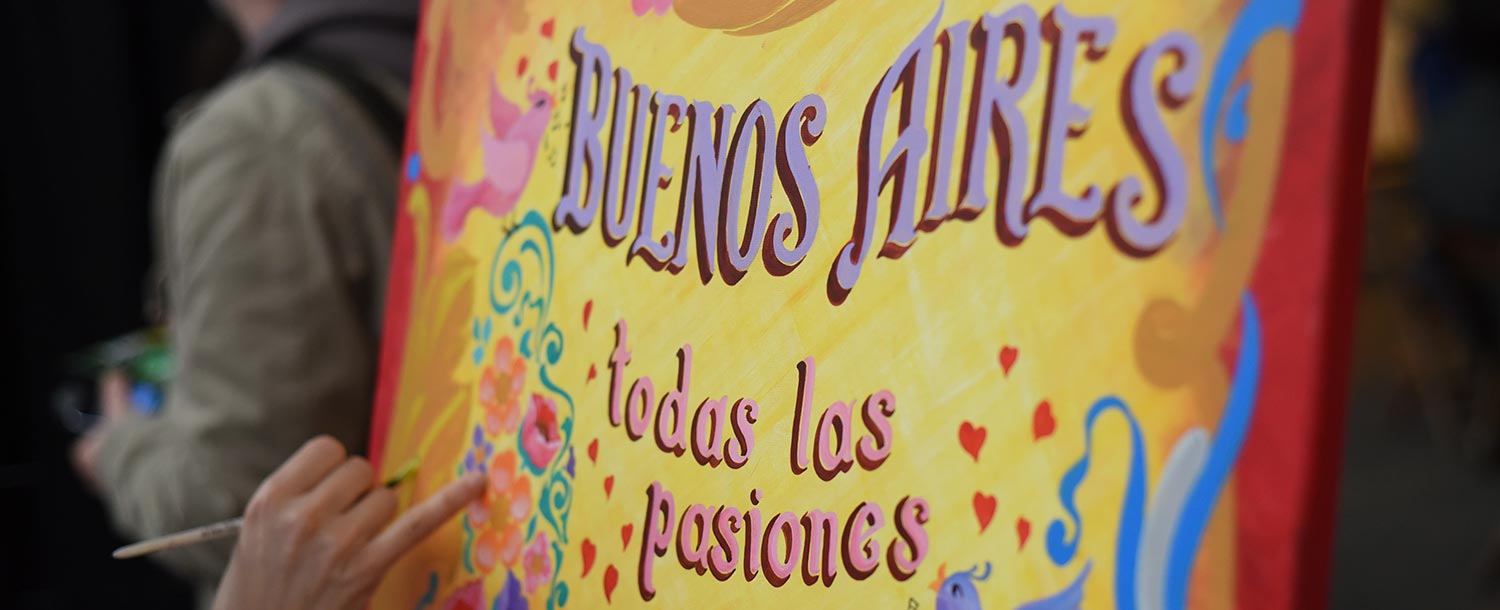

Fileteado emerged in the same original social context as the tango: the working class neighbourhoods of the 19th century with their carts and markets, newly arrived immigrants and a pride in the growing city. Today its bold colours and floral flourishes evoke nostalgia for Buenos Aires’ past.

Yet, like tango, this art form has continued to reinvent itself and maintain its relevance in a fiercely creative city, where traditions evolve but never die. Now young artists, graphic designers, sign painters and even tattooists are looking to the fileteado as a sign of identity and a source of inspiration.

Gustavo Ferrari, 35, is one of them. He creates traditional pieces but also tries to break the mould, sometimes toning down the bright colours with black and white designs, introducing characters and other motifs.

He took up the art at the age of 18, partly inspired by the history degree he was studying at university - studies that mean that Ferrari’s is well-placed to explain the story of fileteado and its intimate relationship with the city’s visual identity.

This folk art form of humble working class origins was developed by Italian immigrants towards the end of the 19th century to decorate wooden trade carts, first with simple decorations and later incorporating monograms using the initials of owners’ names. The style began to develop its own visual vocabulary with birds, dragons, acanthus flowers, and finally rules regarding the balance of different elements and the materials employed. The tradition then expanded to decorate trucks and public buses – the city’s famous “colectivos” – in the 1920s and 30s, when truck owners would compete to have the most heavily decorated vehicle.

It resurgence in recent years came through the boom in tango tourism, with businesses seeking to identify themselves as traditional and authentic and reached the point where Unesco declared fileteado part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage in the year 2015.

And if we paint it on ourselves?

A big development has been the jump from moving vehicles to moving bodies. Gustavo Ferrari has designed tattoos for visitors from all over. The pioneer of this trend was Claudio Momenti, of Lucky Seven tattoos in Recoleta’s Bond Street Arcade, a self-taught tattooist who was looking for his own identity: “Fileteado is part of the local culture and it’s a style of ornamentation you can use to express something personal: your club, your family, your neighbourhood,” he says. “It’s not nostalgic for me, it’s something very uplifting.”

It was no easy challenge to incorporate the fileteado lines into the world of tattoos, and no one was very keen to help him at first. “The few masters who were around at that time were very closed. They didn’t want to teach me.” Momenti now attracts attention at international conventions, where the fileteado has become a recognised style in the tattooing canon.

From Argentina to the World

Alfredo Genovese was perhaps the artist who most saw the potential of the fileteado to expand to different media. He learned from the late masters León Untroib (1911 - 1994) and Ricardo Gomez (1926 - 2011), and started, he says, simply because “it was something rich and complicated that no one else was interested in at the time, and that had a lot of potential to be brought up to date.” And he’s certainly brought it up to date, creating work for major brands including limited edition sports shoes for Nike to bottles for Coca-Cola and Evian, “It feels nostalgic because it’s done by hand,” he says, “but I don’t think of it as something nostalgic; it’s totally current and relevant.”

After studying at Buenos Aires’ School of Fine Arts in the 1980s, he travelled the world to see if anything similar to fileteado existed elsewhere. His conclusion? There was nothing quite like it. Always seeking new challenges, he considers that an aeroplane would make the next perfect canvas for his work. “It would be a mobile work of art with huge reach,” he says, and without doubt there could be nothing more fitting than taking this humble art form that began on carts and carriages into the sky.